Americana is a collective term for artifacts related to the history, geography, folklore and cultural heritage of the United States of America. It is generally defined as any collection of materials and things concerning or characteristic of the United States or of the American people; in its broadest sense, Americana is representative or even stereotypical of American culture as a whole.

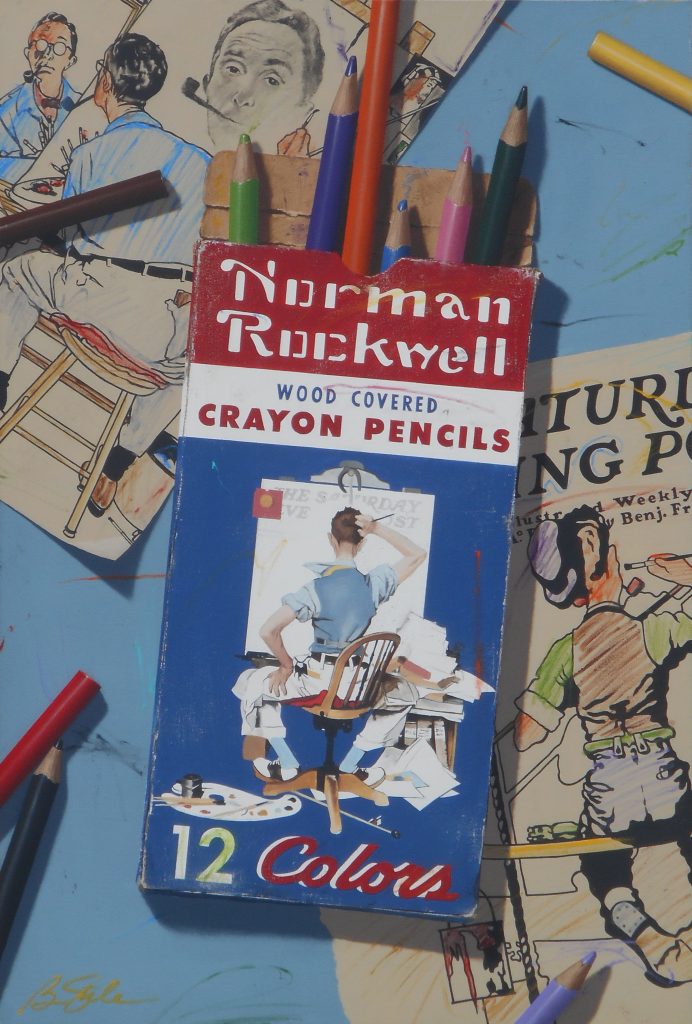

Norman Percevel Rockwell (February 3, 1894 – November 8, 1978) was an American author, painter and illustrator. His works have a broad popular appeal in the United States for their reflection of American culture. Norman Rockwell was a prolific artist, producing more than 4,000 original works in his lifetime. Most of his works are either in public collections, or have been destroyed in fire or other misfortunes. Rockwell was also commissioned to illustrate more than 40 books, including Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn as well as painting the portraits for Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, as well as those of foreign figures, including Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru. His portrait subjects included Judy Garland. One of his last portraits was of Colonel Sanders in 1973. Fun fact: The first Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise opened on September 24, 1952 in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Andy Warhol born Andrew Warhola; August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987) was an American artist, director and producer who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art. His works explore the relationship between artistic expression, advertising, and celebrity culture that flourished by the 1960s, and span a variety of media, including painting, silkscreening, photography, film, and sculpture. Some of his best known works include the silkscreen paintings Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) and Marilyn Diptych (1962), the experimental film Chelsea Girls (1966), and the multimedia events known as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966–67).

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, Warhol initially pursued a successful career as a commercial illustrator. After exhibiting his work in several galleries in the late 1950s, he began to receive recognition as an influential and controversial artist. His New York studio, The Factory, became a well-known gathering place that brought together distinguished intellectuals, drag queens, playwrights, Bohemian street people, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy patrons.[2][3][4] He promoted a collection of personalities known as Warhol superstars, and is credited with coining the widely used expression “15 minutes of fame.” In the late 1960s, he managed and produced the experimental rock band The Velvet Underground and founded Interview magazine.

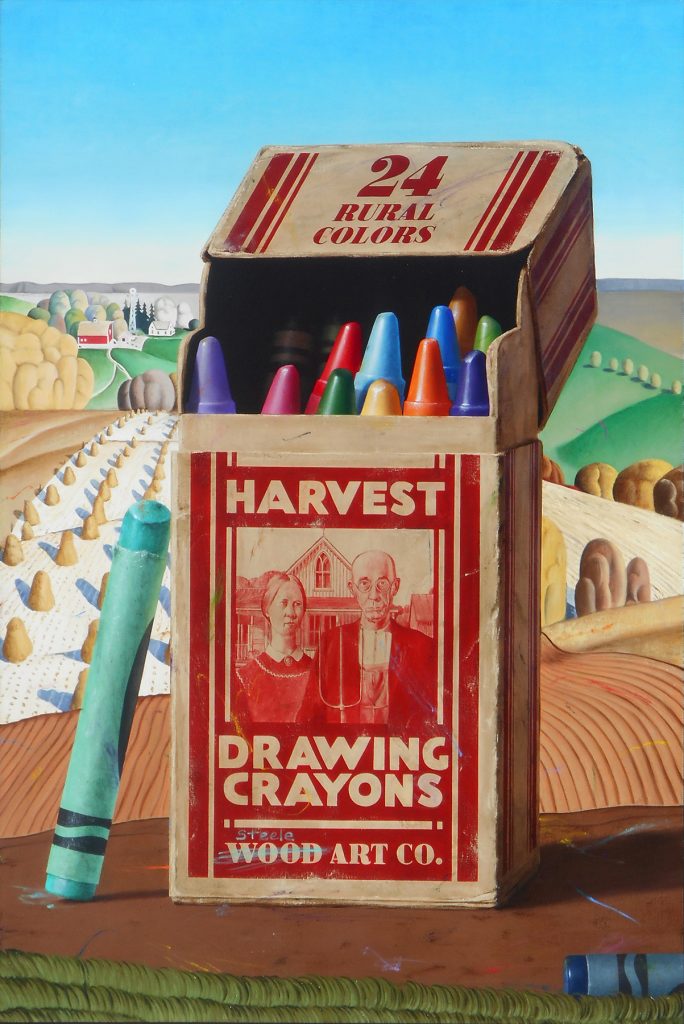

In August 1930, Grant Wood, an American painter with European training, was driven around Eldon, Iowa, by a young painter from Eldon, John Sharp. Looking for inspiration, Wood noticed the Dibble House, a small white house built in the Carpenter Gothic architectural style.[8] Sharp’s brother suggested in 1973 that it was on this drive that Wood first sketched the house on the back of an envelope. Wood’s earliest biographer, Darrell Garwood, noted that Wood “thought it a form of borrowed pretentiousness, a structural absurdity, to put a Gothic-style window in such a flimsy frame house.”[9] At the time, Wood classified it as one of the “cardboardy frame houses on Iowa farms” and considered it “very paintable”.[10] After obtaining permission from the Jones family, the house’s owners, Wood made a sketch the next day in oil on paperboard from the house’s front yard. This sketch displayed a steeper roof and a longer window with a more pronounced ogive than on the actual house, features which eventually adorned the final work.

Wood decided to paint the house along with “the kind of people I fancied should live in that house.”[1] He recruited his sister Nan (1899–1990) to model the woman, dressing her in a colonial print apron mimicking 19th-century Americana. The man is modeled on Wood’s dentist,[11] Dr. Byron McKeeby (1867–1950) from Cedar Rapids, Iowa.[12][13] Nan, perhaps embarrassed about being depicted as the wife of a man twice her age, told people that her brother had envisioned the couple as father and daughter, rather than husband and wife, which Wood himself confirmed (“The prim lady with him is his grown-up daughter”) in his letter to a Mrs. Nellie Sudduth in 1941.[1][14]

Elements of the painting stress the vertical that is associated with Gothic architecture. The three-pronged pitchfork is echoed in the stitching of the man’s overalls, the Gothic window of the house, and the structure of the man’s face.[15] However, Wood did not add figures to his sketch until he returned to his studio in Cedar Rapids.[16] He would not return to Eldon again before his death in 1942, although he did request a photograph of the home to complete his painting.[8]

Nighthawks is a 1942 painting by Edward Hopper that portrays people sitting in a downtown diner late at night. It is Hopper’s most famous work and is one of the most recognizable paintings in American art. Within months of its completion, it was sold to the Art Institute of Chicago for $3,000, and has remained there ever since.

Starting shortly after their marriage in 1924, Edward Hopper and his wife, Josephine (Jo), kept a journal in which he would, using a pencil, make a sketch-drawing of each of his paintings, along with a precise description of certain technical details. Jo Hopper would then add additional information in which the themes of the painting are, to some degree, illuminated.

A review of the page on which “Nighthawks” is entered shows (in Edward Hopper’s handwriting) that the intended name of the work was actually “Night Hawks”, and that the painting was completed on January 21, 1942.

Jo’s handwritten notes about the painting give considerably more detail, including the interesting possibility that the painting’s evocative title may have had its origins as a reference to the beak-shaped nose of the man at the bar:

Night + brilliant interior of cheap restaurant. Bright items: cherry wood counter + tops of surrounding stools; light on metal tanks at rear right; brilliant streak of jade green tiles 3/4 cross canvas at base of glass of window curving at corner. Light walls, dull yellow ocre [sic] door into kitchen right. Very good looking blond boy in white (coat, cap) inside counter. Girl in red blouse, brown hair eating sandwich. Man night hawk (beak) in dark suit, steel grey hat, black band, blue shirt (clean) holding cigarette. Other figure dark sinister back at left. Light side walk outside pale greenish. Darkish red brick houses opposite. Sign across top of restaurant, dark Phillies 5c cigar. Picture of cigar. Outside of shop dark, green. Note: bit of bright ceiling inside shop against dark of outside street at edge of stretch of top of window.

The four anonymous and uncommunicative night owls seem as separate and remote from the viewer as they are from one another. (The red-haired woman was actually modeled by the artist’s wife, Jo.) Hopper denied that he purposefully infused this or any other of his paintings with symbols of human isolation and urban emptiness, but he acknowledged that in Nighthawks “unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

Roy Fox Lichtenstein (/ˈlɪktənˌstaɪn/; October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997) was an American pop artist. During the 1960s, along with Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and James Rosenquist among others, he became a leading figure in the new art movement. His work defined the premise of pop art through parody.[2] Inspired by the comic strip, Lichtenstein produced precise compositions that documented while they parodied, often in a tongue-in-cheekmanner. His work was influenced by popular advertising and the comic book style. He described pop art as “not ‘American’ painting but actually industrial painting”.[3]

Rather than attempt to reproduce his subjects, Lichtenstein’s work tackled the way in which the mass media portrays them. He would never take himself too seriously, however, saying: “I think my work is different from comic strips – but I wouldn’t call it transformation; I don’t think that whatever is meant by it is important to art.”[28] When Lichtenstein’s work was first exhibited, many art critics of the time challenged its originality. His work was harshly criticized as vulgar and empty. The title of a Life magazine article in 1964 asked, “Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.?”[29] Lichtenstein responded to such claims by offering responses such as the following: “The closer my work is to the original, the more threatening and critical the content. However, my work is entirely transformed in that my purpose and perception are entirely different. I think my paintings are critically transformed, but it would be difficult to prove it by any rational line of argument.”[30] He discussed experiencing this heavy criticism in an interview with April Bernard and Mimi Thompson in 1986. Suggesting that it was at times difficult to be criticized, Lichtenstein said, “I don’t doubt when I’m actually painting, it’s the criticism that makes you wonder, it does.”[31]

Sundance began in Salt Lake City in August 1978, as the Utah/US Film Festival in an effort to attract more filmmakers to Utah.[3] It was founded by Sterling Van Wagenen (then head of Wildwood,[4] Robert Redford’s company), John Earle (serving on the Utah Film Commission at the time). The 1978 festival featured films such as Deliverance, A Streetcar Named Desire, Midnight Cowboy, Mean Streets, and The Sweet Smell of Success.[5] With chairman Robert Redford, and the help of Utah Governor Scott M. Matheson, the goal of the festival was to showcase strictly American-made films, highlight the potential of independent film, and to increase visibility for filmmaking in Utah. At the time, the main focus of the event was to conduct a competition for independent American films, present a series of retrospective films and filmmaker panel discussions, and to celebrate the Frank Capra Award. The festival also highlighted the work of regional filmmakers who worked outside the Hollywood system.

Several factors helped propel the growth of Utah/US Film Festival. First was the involvement of actor and Utah resident Robert Redford, who became the festival’s inaugural chairman. By having Redford’s name associated with the festival, it received great attention. Secondly, the country was hungry for more venues that would celebrate American-made films as the only other festival doing so at the time was the USA Film Festival in Dallas (est. 1971). Response in Hollywood was unprecedented, as major studios did all they could to contribute their resources.

In 1981, the festival moved to Park City, Utah, and changed the dates from September to January. The move from late summer to midwinter was done by the executive director Susan Barrell with the cooperation of Hollywood director Sydney Pollack, who suggested that running a film festival in a ski resort during winter would draw more attention from Hollywood. It was called the US Film and Video Festival.